The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the main stabilizing ligaments in the knee. It is a ligament that connects the thigh bone (femur) to the leg bone (tibia). It controls abnormal motion of the thigh bone and the upper end of the leg bone.

An injury to this ligament frequently results in knee instability, that is an abnormal shifting of the knee during cutting, turning, and pivoting actions required during athletic activity.

ACL injury typically occurs during athletics where jumping, pivoting and rapid change of direction occurs. Football, basketball, lacrosse, soccer, and skiing are some sports known to have high ACL injury rates. Contrary to popular belief, the ACL can tear without contact, the so-called non-contact mechanism. In this case the ligament, which is dense fibrous tissue, fails with a twisting mechanism. This non-contact injury occurs more commonly in female athletes. Many factors have been investigated to try to explain why women athletes are more prone to tearing their ACL with a non-contact mechanism. Hormonal differences, a smaller bony notch where the ACL is positioned, differences in muscle strength, and differences in how male and female athletes land after a jump have all been felt to play a role in this observed increase in ACL tears in females.

Typical symptoms of an ACL tear include pain, immediate difficulty with walking and sensation of knee instability. Additionally, a ‘pop’ is often heard and swelling often develops quickly.

After a thorough history and physical exam, the diagnosis of a torn ACL can be made. A well-trained orthopaedic sports medicine physician can make an accurate diagnosis by doing an exam that tests the competency of this ligament. The physician will usually obtain X-rays to check for any small fractures but often an MRI is obtained. The MRI will confirm the tear of the ACL but more importantly will check for the presence of other soft tissue injuries to the knee known to occur with an ACL tear. These other injuries include tears of the medial or lateral meniscus (“torn cartilage”) as well as the joint surface.

Treatment of ACL Tears

The treatment of ACL tears is highly individualized. After the ACL tears, it has a very poor blood supply and the ability for the ligament to heal is limited. Some patients will require surgery while others can be treated with non-surgical methods including bracing and knee rehabilitation. The decision for treatment should be a discussion between the surgeon and patient examining all the injuries that have occurred, the demands of the patient, and athletic and work requirements. In a general sense, patients who wish to remain highly athletic, have torn cartilage, or are not willing to change their active lifestyle will be candidates for surgery.

Patients who are sedentary or are willing to quit participation in cutting and pivoting sports and who do not have any other joint damage may not require surgery. Some patients will require surgery because they have instability with walking and turning despite giving up athletic sports. There is no “age limit” to when surgery is considered. There are many older, masters-level athletes in their 5th, 6th, and 7th decade of life who are very active and wish to continue their athletic interests and are candidates for surgery.

Non-operative treatment means that you and your surgeon have decided to try a period of rehabilitation to strengthen the muscles around the knee with the hopes of improving knee stability. This treatment will not ‘heal’ the ACL tear but in the cases of milder instability, strengthening the muscles may help to avoid the instability problems that occur with an ACL tear.

Operative Treatment “Surgery” for ACL Tears

Almost all active patients and athletes will require surgery to repair the torn ACL. As mentioned before, the ACL has limited ability to heal and simply sewing the torn ends will not be successful. Modern ACL surgery requires the use of another tendon called a ‘graft’ to be used to substitute for the torn ACL.

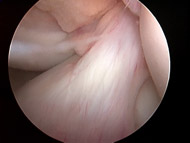

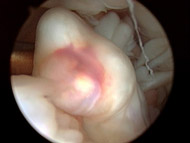

These grafts are inserted into the knee with the use of an arthroscope. The ‘scope’ is a very small lens that placed into the knee joint and is connected to a camera and monitor so the surgeon can examine and operate on the knee with less invasive techniques (see Figures 1A and B).

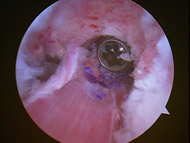

The most common grafts used for ACL reconstruction include the patellar tendon, the hamstring tendons, the quadriceps tendon and a number of donor or cadaver grafts taken from a donor, called “allografts” (see Figure 2).

There are pluses and minuses with each graft and scientific evidence shows no superiority of one graft over another. Surgeons who do a high volume of ACL reconstructions will feel comfortable with a number of grafts and the graft selected can be individualized to the patients past history of knee problems, activity demands, and other associated knee problems.

Rehabilitation After Surgery

Rehabilitation will focus on restoring range of motion, protecting the surgery, and minimizing muscle atrophy. Typically a brace and crutches with protected weight-bearing are utilized for several weeks. The patient will progress to strengthening exercises and more sport-specific training. Most patients are allowed to return to sports between 7 to 9 months. The use of a brace when returning to sports is individualized and there is no scientific evidence that braces prevent ACL injury.

Complications with Treatment

When patients choose non-operative treatment the most common complication is recurrent knee instability. This means that the knee is not reliable and gives out with turning sports. This has the small risk of causing increasing damage to the joint surface and menisci (cartilage).

Complications with surgical reconstruction are uncommon but do occur. The major complication is also recurrent instability or graft rupture in 8 to 10 percent of cases. This may require additional surgery.

Other complications include numbness in the front of the knee that typically requires no additional treatme