Shoulder instability describes a range of conditions affecting the gleno-humeral joint, that part of the shoulder in which the head of the humerus, the upper bone in the arm, meets the glenoid, the cup-shaped shallow socket of the scapula. This is the main shoulder joint.

The shoulder joint is held in place and supported by the rotator cuff, a complex of muscles and tendons; the labrum, a rim of cartilage that surrounds the glenoid; and a capsule of tissue that surrounds the joint composed of ligaments and synovial membrane. Failure in any or all of these structures can lead to the looseness that is diagnosed as shoulder instability.

In normal individuals, the ball portion of the joint moves approximately one inch in a forward or backward direction within the socket. Some people with shoulder instability have a greater range of movement, yet experience no problematic symptoms. Those patients who seek medical care for shoulder instability usually have either a partial dislocation, in which the ball becomes partially dislocated from the socket, or a complete dislocation of the shoulder, in which the ball moves fully out of the socket. Micro-instability may occur in overhead athletes whose throwing activity results in labral tear and capsular or rotator cuff tear.

Partial and complete dislocations may occur either as the result of a single traumatic event, as when a football player makes a tackle or as the result of a motor vehicle accident, or, in a person with inherent looseness in the joint, as a result of repetitive activities such as throwing or swimming. This latter group is described as having loose-jointed lax shoulders and are at risk for non-traumatic shoulder instability because they have unusually elastic collagen, allowing the joint to have greater degrees of movement or looseness.

There is also a small subset of patients who have what is described as voluntary instability, which may be either positional – as when a diver raises his arms and the shoulder pops out of place – or muscular, in which the patient can control the joint at will.

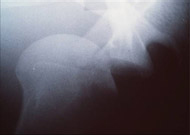

While traumatic dislocation is an immediately apparent medical emergency caused by single traumatic episode that causes the shoulder to completely dislocate, patients who do not have traumatic dislocation, nor any history of dislocation may simply experience a sensation of looseness or instability, especially with activities that require them to raise their arms overhead (see Figures 1A and B). Others may simply have pain in the joint, which can be secondary to a labral tear or to rotator cuff injury with a partial or complete tear.

Treatment

Treatment for shoulder instability is based on a variety of factors including the severity of the condition, and the patient's age, activity level, occupation, and natural degree of looseness in the joint.

Regardless of patient type, prior to initiating treatment the orthopaedic surgeon does a thorough history and physical examination. Where indicated, additional information is obtained through X-ray images and MRI. A traumatic dislocation is extremely painful, but once realignment is achieved, whether on the playing field or in the emergency room, relief is instantaneous. Traumatic dislocations have a high recurrence rate in young patients and thus early repair is considered if the activity is to be continued. Patients after the age of 40 have low recurrence rates and can usually be treated non-operatively. Older patients may tear the rotator cuff during the dislocation and thus usually require an MRI. If a cuff tear is seen, repair is considered.

Patients with multidirectional instability or loose-jointed-ness are usually advised to try a regimen of rehabilitation exercises. If the muscles and tendons that support the shoulder can be made to work more efficiently, the joint will have greater stability. Some researchers have reported a success rate as high as 80 percent in this subset of patients. If an exercise program fails, the orthopaedic surgeon will probably recommend an open surgery (versus arthroscopic treatment) in these loose jointed patients with multidirectional instability.

Patients with voluntary or positional instability are counseled on activity modification and taught to strengthen their muscles. However, athletes with positional instability may be candidates for surgery to protect the shoulder in the face of continued stress that will be placed on the joint.

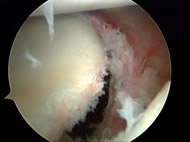

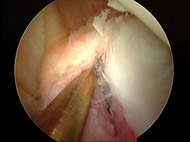

When surgery is necessary, whether it is performed as an open procedure or using arthroscopy, the techniques are similar. The orthopaedic surgeon realigns the joint in a process called reduction, identifies the labrum and capsule that has loosened or pulled away from the bone, and reattaches it with sutures (Figure 2).

In effect, the capsule that contains the joint is tightened and restored to as normal tension as possible. The goal is to stabilize the glenohumeral joint while retaining range of motion.

Arthroscopic approaches have improved so much over the past decade that, provided there is no other injury present, the majority of traumatic dislocations can be treated with this technique. The arthroscope is a small lens that can be placed into the shoulder thru very small incisions. This scope is connected to a camera dn monitor so that the surgeon can see and operate with very minimally invasive incisions and technique (see Figures 3A, 3B, and 3C).

Patients undergoing arthroscopic surgery for shoulder instability usually do not stay overnight in the hospital. Local anesthesia and sedation is used during the procedure.

Some patients with traumatic dislocation may require open surgery, especially if their injury occurs in conjunction with a fracture of the glenoid socket or the humeral head. Open surgery may be performed in patients who are undergoing a revision procedure for traumatic dislocation. If the joint capsule is no longer reparable, the surgeon may need to add tissue to thicken this supportive membrane. If the subscapularis tendon, an integral part of the rotator cuff has torn off and cannot be sutured together, a tendon transfer may be required.

Young patients with recurrent traumatic dislocation who wish to return to athletic activity are also candidates for surgical treatment, as they have a recurrence rate of over 90 percent depending to a degree on the activity they are performing.

Complications and Recurrence

Surgical treatment for shoulder instability is generally considered quite safe. Performed by an experienced orthopaedic surgeon, the risk of infection, nerve or vascular injury, is minimal.

Following surgery and throughout rehabilitation the patient is monitored for stiffness. Occasionally arthroscopic release of the capsule is necessary to restore motion. (Individuals with a prior high number of dislocations are likely to develop some degree of arthritis in the joint, secondary to the trauma of the dislocation and reduction.)

The incidence of recurrence of either a partial or complete dislocation that is treated non-surgically is largely dependent on the patient's age. In patients under 20 years old who experience a traumatic dislocation, the recurrence rate is as high as 95 percent – a phenomenon that is probably related to natural looseness in the joint and return to activities that place stress on the joint. Among patients age 40 and older the recurrence rate drops dramatically, to about 15 percent, owing to a natural tightness in the joints that develops with age and changes in activity level.

Recurrence rates in patients who undergo surgery vary depending on the patient's level of activity. However, overall the results are quite good, with a general recurrence rate of less than 5 percent for those with surgical treatment of traumatic dislocation. Among patients with multidimensional, loose-jointed lax shoulders, the rate is closer to 10 percent.

The orthopaedic surgeons at the UConn Musculoskeletal Institute also treat a certain number of patients whose surgical treatment has failed. Repeat surgery can be performed, although the success rate is somewhat lower, roughly 85 percent of patients with traumatic instability can achieve stability. Among patients with multidirectional instability who are seeking repeat surgical treatment, the success rate is approximately 50 percent.

Rehabilitation and Recovery

Whether the orthopaedic surgeon uses an arthroscopic approach or performs an open procedure, patients who undergo surgery have a similar recovery period. During the first four weeks a sling is worn to protect the shoulder and restrict mobility as the tissue heals. Gentle range-of-motion exercises are performed. After this period the patient begins a program of strengthening exercises. Most people can return to athletic activity that places stress on the shoulder after four months of rehabilitation.