Climate Change and Increasing Moisture

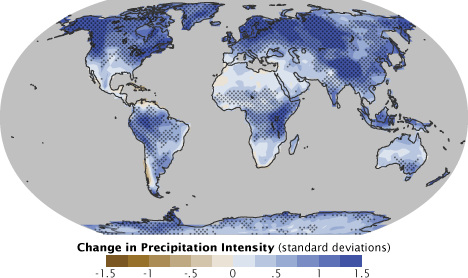

Resilient building is becoming increasingly important due to climate change. Sea level rise, increased abundance and/or severity of storms, and overall increased precipitation intensity are expected for many areas of the U.S. including all states hit by Hurricane Sandy on October 22-31 2012 (Figure 1).

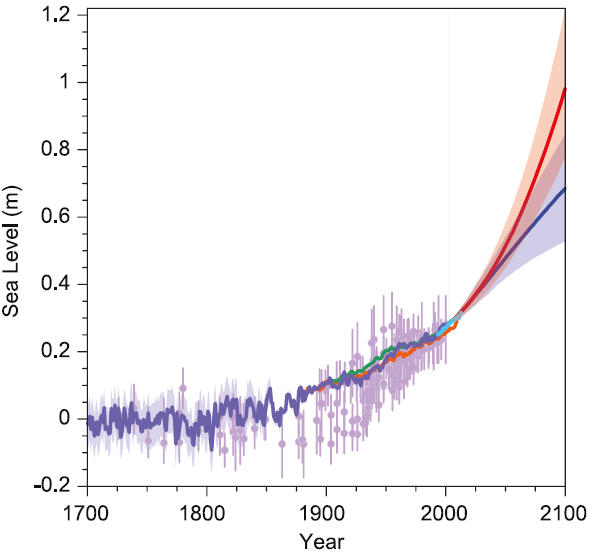

Annual precipitation intensity in the U.S. is expected to increase the most in New England, where the frequency of 2 inch rainfall events has increased since the 1950s, and storms once considered a 1 in 100 year event are now likely to occur twice as often (NRCC 2015). According to the 2014 International Panel on Climate Change Report, under estimated “business as usual” emissions scenarios sea level is expected to rise by 52-98 centimeters by year 2100. Even with aggressive emissions reductions sea level is expected to rise 28-61 centimeters (Figure 2).

Sea level rise, more abundant and/or severe storms, and increasing precipitation intensity means more flooding and wetness indoors. Therefore, water damage in buildings is becoming an even larger concern for New England due to climate change.

>>>More about climate change from the New England Aquarium

Moisture, the Indoor Environment, and Health

People spend most of their time indoors and therefore individuals’ comfort, health, and productivity depends heavily on maintaining a healthy living environment indoors. Wetness and moisture indoors has health implications including the possibility of exposure to mold and bacteria and their components and to outgassing from the degradation of wet building materials (Institute of Medicine 2011).

Rebuilding with Resiliency to Storms and Flooding

Resilience is defined by the Resilient Design Institute as, “the capacity to adapt to changing conditions and to maintain or regain functionality and vitality in the face of stress or disturbance. It is the capacity to bounce back after a disturbance or interruption of some sort” (http://www.resilientdesign.org/).

In order adapt to climate change and increase building resiliency to weather hazards it is important to build or rebuild in ways that will reduce damage and also may save money in the long run. According to the Multihazard Mitigation Council (MMC) of the National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS), a dollar spent on mitigation saves society an average of $4 (MMC and NIBS 2005). Flood proofing homes is a good way to mitigate water damage from severe weather and flooding. Elevating buildings (and critical electrical equipment) above flood levels is an effective way to protect against flooding (and power outages). However, there are other things you can do to reduce the risk of severe water damage in your home. This includes building floodwalls, berms, or levees, sealing a building to keep floodwaters out, or replacing building materials that are below flood levels with materials resistant to water. Preventing flood waters from entering your home, and controlling moisture indoors is critical for maintaining a healthy living environment.

>>>See William Turners Presentation for More Information

>>>>Building Science Moisture and Mold Mitigation Guidance video by William A Turner, MS, PE; June 21, 2009 National Environmental Health Association Pre-Conference Workshop Multimedia Module

References:

Graham, Steve, Claire Parkinson, Mous Chahine, and Robert Simmon. “The Water Cycle and Climate Change.” NASA Earth Observatory. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, 1 Oct. 2010. Web. 27 Jan. 2015. http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/Water/printall.php. Institute of Medicine. Climate Change, the Indoor Environment, and Health. Washington, D.C.: National Academies, 2011. Print.

Institute of Medicine. Climate Change, the Indoor Environment, and Health. Washington, D.C.: National Academies, 2011. Print.

IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

MMC and NIBS. National Hazard Mitigation Saves: An Independent Study to Assess the Future Savings from Mitigation Activities, Vol. 2 Study Documentation. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Building Sciences, 2005. FEMA, 2005. Web. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.nibs.org/resource/resmgr/MMC/hms_vol1.pdf.

NRCC, and NRCS. “Extreme Precipitation in New York & New England: An Interactive Web Tool for Extreme Precipitation Analysis”. Cornell University, 2010-2015. Web. 15 Jan. 2015. http://precip.eas.cornell.edu/.