The goal of this research study is to identify genes and regulatory elements on chromosomes that cause cherubism. Together with our collaborators we also study blood samples and tissue samples from patients to learn about the processes that lead to this disorder. The long-term goal of researchers involved in this study is to find mechanisms to slow down bone resorption in cherubism patients.

About the Cherubism Study

What is cherubism?

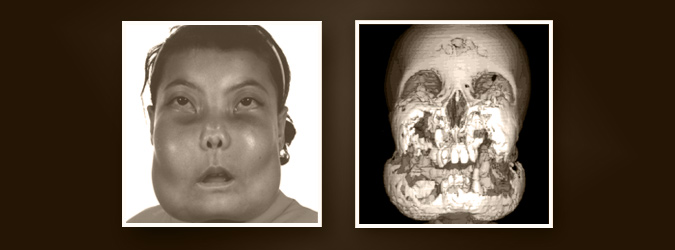

Cherubism is a very rare bone disorder where bone gets resorbed only in the jaw bones (mandible and maxilla). The resulting cavities in bone fill up with soft fibrous (fibro-osseous) tissues that can expand and push the bony shells apart, which gives patients with progressed cherubism the characteristic facial appearance. Bone resorption (cherubism lesions) in this disorder is always symmetrical in the mandible, the maxilla or both. This distinguishes cherubism from similar disorders. As cherubism progresses, the lesions can invade the eye sockets (inferior and/or lateral orbital walls) and displace the eye balls and push down the eyelids. As a result the sclera (white of the eye) below the iris becomes visible and patients have an upward gazing appearance (cherubic look) which gave the name to this fibro-proliferative bone disorder.

Cherubism typically appears between ages of 2-7 years. It is often diagnosed during dental evaluations. At early stages cherubism is accompanied by lymph node swelling. Proliferation of the fibro-osseous tissue typically stops after puberty and in many the soft tissue in the cherubic bone cavities are replaced by new bone.

What do we know about the genetics of cherubism?

In 2001 mutations for cherubism in a gene called SH3BP2 on chromosome 4 were found. Cherubism can be inherited and run in families. Most of the familial cherubism is inherited in an autosomal dominant mode. This means that one copy of chromosome 4 carries the normal copy of SH3BP2 and the other copy of chromosome 4 the mutated SH3BP2.

There are patients with cherubism who do not have any family history of cherubism. Their parents have a normal set of SH3BP2 genes and the patient developed the mutation spontaneously during early embryonic development, as a so called de novo mutation. One explanation for different patients developing the same mutation is that the SH3BP2 gene may be located in a genetic hot spot where the likelihood for a mutation is higher than in other chromosomal regions.

There is also the autosomal recessive form of cherubism for which no mutation has been published yet. Both parents have one copy of a mutated gene (yet unknown) and their children have a 25% chance to inherit both mutated copies of this gene. Only individuals with 2 mutant copies of the gene will develop cherubism. In most cases the parents have common ancestors.

There are yet other patients who have been diagnosed with cherubism who do not have the recessive form of cherubism nor a mutation in SH3BP2. We believe there are other genes that can cause CMD or a CMD-like condition (= genetic heterogeneity) and we do our best to find those genes.

Cherubism-like phenotypes can be associated with the Noonan Syndrome (NS) spectrum. Several genes have been associated with NS.

SH3BP2 codes for a protein that helps other proteins come together (adapter protein) as a complex to carry signals from one cell to another or within the cell. In cherubism this SH3BP2 protein that carries the mutation is highly active for longer than normal because it cannot be degraded.

Can cherubism be inherited?

The current evidence is that all known cherubism mutations are germline mutations, which means that they can be passed on to offspring.

Do we treat cherubism?

No, we do not treat cherubism. We and our collaborators at the University of Missouri-Kansas City perform basic research to understand what happens in bone cells that lead to this characteristic bone phenotype. Based on this knowledge we hope that treatment can be developed in the future.

Why should I participate in such a genetic study?

Although we know some mutations in the SH3BP2 gene, we are looking for more cherubism patients to participate. The goal is to identify additional mutations and additional genes that can lead to cherubism. This knowledge will help to better understand the molecular pathways of cherubism and what regulates the initiation and maintenance of cherubic lesions.

Your participation will help to reach our goal.

Will I directly benefit from this study?

You will not directly benefit from the results of this study.